| |

| Acorn junction (courtesy of Exeter City Council) |

St Leonard's is a beautiful part of a beautiful city. I am writing this blog to encourage residents and visitors to look at their surroundings.

Monday, 22 December 2014

Fifty years ago, the Acorn looked like this

A view of the edge of St Leonard's in the 1960s

Two recognisable buildings in the distance. The double-decker bus in top left is just passing the Magdalen Chapter hotel; at the time the building was the Exeter Eye Infirmary. At the top on the right is the roof of one of the houses in Good Shepherd Drive

Saturday, 6 December 2014

Magdalen Road Christmas Fair 2014

Pictures from the Magdalen Road Christmas Fair, Saturday 6th December 2014

Were you there? Are you in any of the pictures?

Were you there? Are you in any of the pictures?

Saturday, 8 March 2014

Have you ever looked at the hedges in St Leonard’s?

If the Tardis carried you back to St

Leonard’s in the eighteenth century or earlier, the roads of our neighbourhood

would be lined with hedges, to protect the local farmers’ livestock from

travellers, and vice versa. So our

oldest roads, Wonford Road,

Heavitree Road,

Magdalen Road,

Topsham Road

and Matford Lane

would have been muddy tracks with a hedgerow and stone walls on each side,

interspersed with gates and farm buildings.

Those hedges would have been like many in rural Devon,

a dense barrier of native trees and shrubs, tended by regular cutting and

periodic hedge-laying, with hand-tools, of course. There is a modern example of hedge-laying at

the further end of Bromhams Farm football field.

|

| At the junction of Matford Lane and Wonford Road the hedge is a survivor from the old hedgebank, hidden behind the scrub. |

The nineteenth century saw parts of these

roads being developed for houses, with the loss of most of the ancient hedges,

though boundaries followed the old lines.

But the houses that were built needed to mark their boundaries, and new

hedges were planted. Unfortunately, it

is hard to date when local hedges were planted, but some have been with us for

a century or more. (In rural areas,

there are rules of thumb for estimating the age of a hedgerow, based on the

number of species of tree in a given length, but those rules don’t work in towns

and cities.)

The process has continued to the present

day, with many more recent household boundaries marked by hedges on their own,

or with walls or fences. It seems

strange, since a hedge demands more maintenance than a fence or wall does, but

hedges give us a link back to the rural past, and have many other benefits as

well.

|

| A section of wall with hedge on top (Wonford Road) |

Now look more closely, and you will see how

every hedge displays some individuality.

First, what kind of tree has been planted? Is there one species, or two, or more? Are they mixed in a systematic way? When I was researching this, I came across a

hedge that is being repaired where the side facing the road has been planted

with a row of one species of tree, and the side facing the garden with a

second. A mixture may also be the result

of new species colonising the hedge, as happens on farms, and provides the

basis for estimating the age of the hedge.

Privet is a popular choice of tree, with laurel and holly as alternative

evergreens. There are several beech

hedges, liked because the leaves turn brown in the autumn and are only shed in

the spring. There’s a fine example at

County Hall. One or two gardens have

more exotic hedges, using flowering shrubs such as roses (10 points for one of

these). And, yes, we have some hedges of

the fast-growing, notorious, and very thirsty, Leyland Cypress.

|

| Beech hedge at County Hall |

Second, how is the hedge tended? Is it cared for? After two or three years of neglect, the

hedgerow trees start to look less like a hedge and more like a wilderness. If it is cared for, then has it been trimmed

with geometrical precision to look like a wall?

Or does it have some curving shape or irregularity? Does the hedge match the hedges on either

side? Or have different owners imposed

individual styles on theirs? You’ll find

high hedges and low hedges along local streets, creating an interesting urban

landscape. Maybe that is what inspired

an estate agent to advertise with the line: "Set amidst the grand avenues

of Exeter's

premier residential district".

Then, is it really a hedge, or a hedge-like

boundary? In suburban gardens many of us

prefer variety to monotony, so mark the boundary with several shrubs or small

trees, cut to the rough shape of a hedge, but really forming a harmonious

backdrop to the planting of the garden.

Look out for front gardens which are marked by a row of trimmed shrubs

of assorted species. When I came to live

in this area, an older resident apologised to me for the shape of one of his

front garden shrubs, which he had trimmed into the shape of a cube. But instead of having edges which were

horizontal and vertical, it leaned at a marked angle. He said that, twenty years on, it was still

recovering from the effects of the 1962-63 winter, when the weight of snow had

bowed the main trunk.

Hedges can divide gardens into rooms, as

happens in many country houses. On a

smaller scale, car parks are often hidden behind hedges, as happens on the St

Luke’s campus. Not only do the trees

screen the vehicles, but they help reduce pollution.

There are hedges on the hospital site for the same reason. The offices next to the Crown Court have a low hedge for another reason; it protects the wall from careless parking. An extension to the concept of hedges marking rooms is to create windows and doors (25 points for finding one). One example of the latter is at County Hall, and there are others on private houses in St Leonard’s; look out for them.

|

| A low hedge to mark the boundary of a car park, County Hall |

There are hedges on the hospital site for the same reason. The offices next to the Crown Court have a low hedge for another reason; it protects the wall from careless parking. An extension to the concept of hedges marking rooms is to create windows and doors (25 points for finding one). One example of the latter is at County Hall, and there are others on private houses in St Leonard’s; look out for them.

|

| A doorway or arch through a hedge (County Hall/Matford Avenue) |

Besides their aesthetic interest, hedges

are havens for wildlife. Birds nest in

our hedges, so if you have a hedge, please don’t cut it when there are likely

to be nesting birds hidden in the greenery.

They provide corridors around the neighbourhood for a variety of

animals, hedgehogs, squirrels, foxes and rodents. Frogs, toads and newts can be found in them,

along with the occasional snake or slowworm.

Butterflies feed on the hedges, and lay their eggs on some species.

Last, but not least, when we are looking

for trimmed hedges and bushes, there are a few examples of topiary in the front

gardens of the neighbourhood. One is in Magdalen Road. Go and find it!

Monday, 20 January 2014

The Victorian revolution in St Leonard’s

According to Robert Newton, author of the

book “Victorian Exeter”, 1850 was a turning point in the history of the city of

Exeter. His book examines the economic, social and

political development of the city from the 1830s to the turn of the

century. He found several reasons for

the importance of the year, and drew attention to one particular event as

crucial to the revolution.

And it happened in St Leonard’s.

Our revolution was not a violent one, although some blood was shed. In July 1850, the Royal Agricultural Society of

Great Britain held its annual show in our neighbourhood. At the time, St Leonard’s was growing as a desirable place

to live, but there were still many fields, smallholdings, nurseries and small

estates around the large houses. The

Society showground was on a field bounded by Matford Lane to the west, and Wonford Road to the

north; both these roads existed at the time.

The southern boundary was the edge of the Coaver estate, roughly where

there is now an access road to County Hall from Matford Lane, and extended to the line of

the road into Deepdene

Park. At the time this was a field called “Sixteen

Acres”. Later in the 19th century it was referred to as Matford Field. Today, Matford Road and Matford Avenue occupy the field. For centuries, this area was in Heavitree

parish. Changes to the parish boundaries

were made in the 19th century to bring it into St Leonard’s parish.

Holding a national agricultural show in Exeter seems to have been an important element in Exeter’s transition from

a small provincial town to a city of national importance. The city was on the map. People travelled to Exeter from all over the country to attend

and to display both their animals and their inventions. The weekly newspaper, the Exeter Flying Post,

issued a special supplement for the show, which listed many important visitors

and where they were staying. With a view

to publicity, the newspaper could be sent to anywhere in the country in

exchange for five postage stamps (5 old pence).

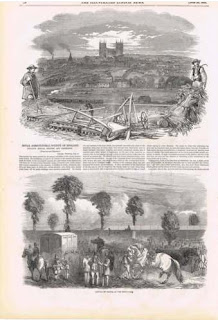

The Illustrated London News, which circulated across the empire,

reported the event with a fanciful picture of a farm worker silhouetted against

a vista of the city, alongside portraits of the prize bulls, and a sketch of

one of the celebration arches put up in the city to welcome visitors.

|

| From the "Illustrated London News" |

In the previous decade, communications

between Exeter

and the rest of the country had improved enormously. The railway had reached Exeter, and in 1850 the first excursion train

came to the city. The city’s economy was

changing too, with councillors who were committed to putting Exeter onto the national stage, and

developing industries such as papermaking and iron foundries. Piped water had come to the neighbourhood in

1833, followed by gas three years later, and improved sewage in the 1840s.

The displays of agricultural equipment on

the Matford Lane

site were a foretaste of the show in the Great Exhibition in Hyde

Park the following year.

New designs of mass-produced plough featured in the sixteen sheds of

implements; numerous steam engines were displayed, ready to be connected to the

latest designs of farmers’ machinery. Show

animals came from all over England

for the event, and there were fourteen sheds for them, each about 250 feet

long. For the intellectual visitors,

Professor Simonds of the Royal

Veterinary College

gave a lecture on “The Structure, Functions and Diseases of the Liver in

Domesticated Animals”. Gripping stuff!

If that was not of interest to you, there

were other events in St Leonard’s

to delight the visitor. The Veitch

nurseries, further east along Wonford

Road, were open to visitors from 6am to 6pm every

day. In a field opposite Parker’s Well

House (presumably on the Royal

Academy for the Deaf

site), there was a circus all week. The

Grand American Circus boasted an Equestrian Troupe of Ladies; tickets were 2

shillings for first class seats, 1 shilling for second class tickets, and 6

pence for a promenade ticket. Children

were half price for the seats. The

grounds of Mount Radford House were open to visitors as well, since the Devon and Exeter Botanical and Horticultural Society was

staging an “Extra Grand Horticultural Fete”.

This would cost you a little more than the circus, at half-a-crown for

adults. (The organisers drew attention

to the fact that there was special provision for carriages.) Tickets for the Grand Agricultural Ball cost

a tear-jerking eight shillings each.

|

| The journal of the RAS included a report on the Exeter show, including this splendid device used for testing threshing machines. (Every home should have one!) |

More ominously, the newspaper reported that

a “swell mob” of criminals was expected to descend on Exeter

for the show – so a crack squad of policemen came from London to deal with the potential problem.

Robert Newton claimed that from 1850

onwards, Exeter’s status in the United Kingdom

started to improve. We in the

neighbourhood can be proud that we hosted the revolution which contributed to

this. It was almost bloodless; the only

blood which was shed was of farm animals, sold to Exeter butchers.

|

| Print of the prize-winning cattle at the show (Illustrated London News) |

Today there is no trace of the show. The temporary half-mile long boundary fence

was quickly taken down, along with thirty sheds and other buildings, and the

field returned to pasture. Fifty years

later, new roads were made, the first seven houses were erected on the field,

five of which still stand (two were destroyed in 1942), and others have been

added since. In 2008 it was added to the

conservation area. But there is still an

open space used by the 1850 show for you and I to enjoy. It is a corner of the County Hall campus in

the corner of Matford Land and Matford Avenue.

There’s a notice to ban “organised ball games”, but nothing banning an

agricultural show. Now, I wonder …!

In the Neighbourhood News, Jan-Feb2015

Addition in January 2017

I have just come across "Putting on a show: the Royal Agricultural Society of England and the Victorian town,c.1840–1876" by Louise Miskell in Agricultural History Review vol 60 pages 37-59

This refers to the Exeter show in several places: she writes: "When Exeter was overlooked in favour of Plymouth in 1865 it was a snub that still rankled, even ten years later when it was recalled that the decision had been arrived at, ‘notwithstanding all that could be urged in favour of the unmistakable and unchallengeable claims of the Cathedral city of the Diocese’. (quoting from Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post, 14 July 1875

There was also controversy about mixing politics with the agricultural show. "At Exeter in 1850, for example, the organization of a ‘political and Protectionist dinner’ during show week invoked disapproval in the liberal London press. The Morning Chronicle’s correspondent noted that, ‘Any event which would have the effect of mixing up a purely agricultural society with party politics is, in the opinion of the principal members of the Royal Agricultural Society, much to be deplored’. The editors of the Mark Lane Express, in contrast, gave generous coverage to the ‘Grand Protectionist Banquet at Exeter’ and to the anti-Free Trade rhetoric of the speakers in its special supplement, published to cover the events of the Exeter show."

She also gives some statistics about the show: It cost the RAS £6570 to put on the show in Exeter, and receipts were £4941, meaning a loss of £1629. A total of 1223 implements and 619 livestock were exhibited; sadly, her sources did not give the attendance figures

In the Neighbourhood News, Jan-Feb2015

Addition in January 2017

I have just come across "Putting on a show: the Royal Agricultural Society of England and the Victorian town,c.1840–1876" by Louise Miskell in Agricultural History Review vol 60 pages 37-59

This refers to the Exeter show in several places: she writes: "When Exeter was overlooked in favour of Plymouth in 1865 it was a snub that still rankled, even ten years later when it was recalled that the decision had been arrived at, ‘notwithstanding all that could be urged in favour of the unmistakable and unchallengeable claims of the Cathedral city of the Diocese’. (quoting from Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post, 14 July 1875

There was also controversy about mixing politics with the agricultural show. "At Exeter in 1850, for example, the organization of a ‘political and Protectionist dinner’ during show week invoked disapproval in the liberal London press. The Morning Chronicle’s correspondent noted that, ‘Any event which would have the effect of mixing up a purely agricultural society with party politics is, in the opinion of the principal members of the Royal Agricultural Society, much to be deplored’. The editors of the Mark Lane Express, in contrast, gave generous coverage to the ‘Grand Protectionist Banquet at Exeter’ and to the anti-Free Trade rhetoric of the speakers in its special supplement, published to cover the events of the Exeter show."

She also gives some statistics about the show: It cost the RAS £6570 to put on the show in Exeter, and receipts were £4941, meaning a loss of £1629. A total of 1223 implements and 619 livestock were exhibited; sadly, her sources did not give the attendance figures

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)