Earlier this year there was a minor frenzy in the press when

a GCSE exam question was posted on social media as being “too difficult” and

“impossible”. It was, of course, a

mathematics question. The question told

pupils that Hannah had a bag containing a total of n sweets of which 6 were

orange. It said the chances of Hannah picking two orange sweets one after the

other was one third and then said “use that” to prove that n²-n-90=0.

Now read on, if you dare; that is the only bit of

mathematical notation in this article. The

question suffered from two things.

First, the setter had not suggested any of the logical stages involved

in translating the words in the problem into mathematics. But, second, the question had introduced that

“awful thing”, a quadratic equation. And

for many people, that is the nightmare remembered of school mathematics. “What’s the use of quadratic equations?” has

become a cry of desperation!

Quadratic equations, like much of mathematics, are tools for

describing what happens in the world in a way which helps the world to be

understood. Learning their name and

shape, or any other bits of mathematics, should be seen as one of those life

skills that one needs to know exists, like knowing that salt contains sodium,

or that the River Thames flows through London – something to know, even if you

don’t use that information very often. To

tell, the truth, even mathematicians will go through their professional lives

without often needing to solve such equations.

If that skill were really needed in everyday life, we would buy

calculators with a button to solve them.

But that doesn’t mean that the equations themselves are irrelevant. And you can find evidence of them in St

Leonard’s.

The first place you will encounter those dreadful equations

is on the roads. When I took the driving

test, the Highway Code gave stopping distances for cars in feet; now it uses

metres, even though the car speeds are still given in miles per hour. So a car travelling at 20mph has a “thinking

distance” of 6 metres, and a stopping distance of 6 metres. Go twice as fast, and a car travelling at

40mph has a thinking distance of 12 metres (twice as much) but a stopping

distance of 24 metres (four times as much).

Look at other speeds: 30 mph has the distances 9 metres for thinking and

14 metres for stopping, and 60 mph has 18 metres (twice as much as thinking at

30mph) and 55 metres (about four times as much for stopping). There’s a rule here: thinking distance is

proportional to the speed; stopping distance is proportional to the square of

the speed. The overall distance is a

quadratic equation depending on the car’s speed. So, be careful when you step into the road

without looking; that car breaking the speed limit may not be able to stop in

time.

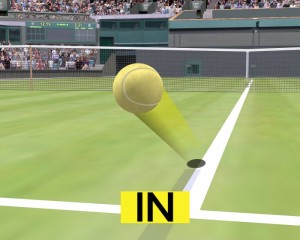

If you have crossed the road safely, wander along to one of

the tennis courts and watch the players; whenever they hit a ball, it will fly

along a path whose height is another quadratic equation. Once the ball leaves the racquet, gravity

pulls it down. So instead of following a

straight line through the air, it follows a curve, and the amount it deviates

from a straight line depends on both the time since it was hit and the square

of that time – yet another quadratic equation.

(That’s what Hawkeye uses at Wimbledon.)

There is also some air resistance, which a more advanced equation will

include. If tennis is not your game, the

flight of a cricket ball at Exeter School, or on the cricket ground at County

Hall, after it has been hit and has lost most of its spin, is also explained by

a quadratic equation. The fielder who

catches the ball has solved that equation!

If you are fortunate to have a pendulum clock at home, then

that depends on a third quadratic equation.

The time it takes for the pendulum to swing is linked to the length of

the pendulum by another quadratic equation.

Grandfather clocks have a pendulum which takes one second to swing,

which means the gears in the clockwork are simple to make, but also means that

the grandfather clock needs a long case.

Back to the streets of St Leonard’s for the final quadratic

equation; you’re bound to find someone chatting on their mobile phone (though

not while driving!). All the electronic

bits and pieces inside that phone needed someone to describe the movement of

electrons using quadratic equations. The

same is true for that noisy radio you hear through an open window. Maybe the designer of that radio shouldn’t

have learnt about quadratic equations!

(Published in St Leonard's Neighbourhood News, September-October 2015. I know that I have used the word "Equation" a little loosely, where "Expression" would be more accurate, but I was writing for a non-mathematical readership.)

No comments:

Post a Comment